Placements for development: creating a new cadre of catalysts

Placements for low-income country workers in top businesses abroad can help Sub-Saharan Africa solve its labour productivity problem.

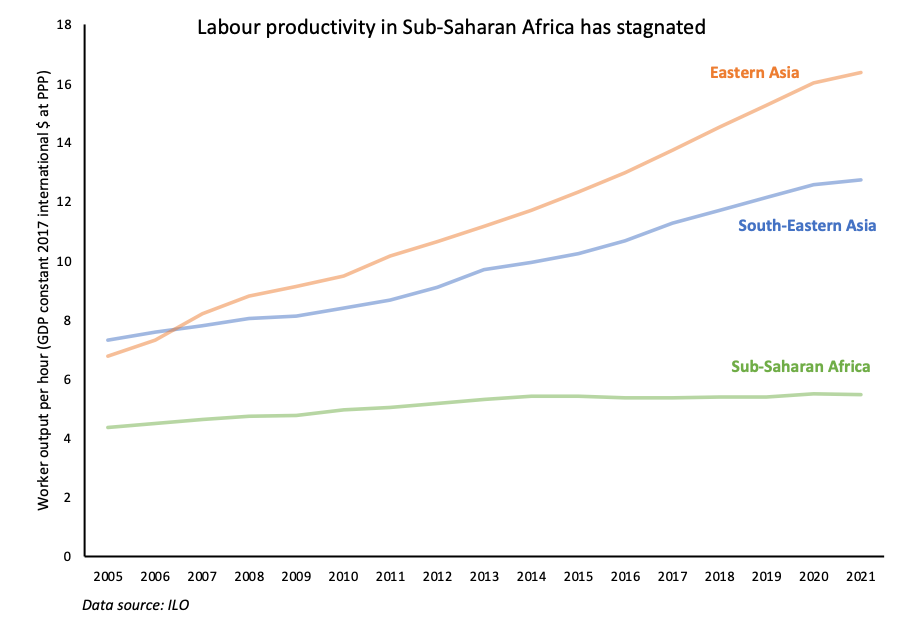

In recent weeks GPI has had a lot to say about labour productivity. So much about the diverging experiences of Sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia can be understood through this lens. Take the chart below. While worker output in Sub-Saharan Africa has stagnated since 2005, it has surged in Eastern and South-Eastern Asia. Exports have boomed and East Asia has become the poster region for economic development.

A big part of the story, as another recent GPI article described, is infant industries learning from their more advanced global counterparts. There were other effects as well, but this process of learning from abroad was crucial for boosting labour productivity. By absorbing the expertise of global leaders, workers in East Asian countries learned to make high quality products at globally competitive prices. Once they managed this, the export orders came flooding in.

One thing is clear: Sub-Saharan African countries need to do everything they can to boost their labour productivity. There are many possible ways to do this, and we should be open to trying a wide range of policies and programmes. But here’s one more idea: placements for promising workers in the top performing businesses in high-income countries.

We are more familiar with the opposite idea. Every year, hundreds of thousands of people from the West travel to Sub-Saharan Africa to work or volunteer, all in the name of international development. At its worst, this manifests as voluntourism, where well-intentioned young people pay to volunteer in orphanages and inadvertently drive demand for orphans. But even for the most useful of these schemes, it is the volunteer who gains most from the experience.

Some of these programmes see technical experts from high-income countries train local workers, like Germany’s Senior Expert Services or the Netherlands’ PUM. Sometimes this happens internally within multinational companies with a presence in low-income countries. Other times it is a part of donor sponsored programmes.

This form of skill building is often valuable, but how about sending workers the other way as well? Such a scheme – let’s call it Placements for Development, or PfD – would see promising technicians, tradesmen or managers from nascent businesses in Sub-Saharan Africa become apprentices or full-blown employees for a set period in top international firms overseas – in the UK, the US, the EU, East Asia, wherever the necessary skills can be learned. Why not give these workers the full experience of what it means to be part of a highly productive, world leading workplace?

The UK, for example, has many top-quality apprenticeship schemes that are world leaders in terms of skill development. Spending time on the Jaguar-Land Rover apprenticeship scheme would undoubtedly help PfD participants build top level technical, organisational and management skills. We know these schemes boost the productivity of its current participants (apprenticeships in the UK typically boost hourly wages by 10-15%, for example see here). It could do the same for citizens of low-income countries.

Having completed PfD, these workers can return to boost domestic industries in their home countries. There is good evidence to suggest that the growth of a new industry in low-income countries is often spurred by a single catalyst; someone with the knowledge, skills and determination to get the industry going. This scheme could create a new cadre of catalysts, increasing the chance of industrial development at home.

PfD would closely reflect the key potential growth sectors of the sending country. For example, if Malawi has a nascent electric motorbike manufacturing sector which is showing potential, then send 50 technicians and project managers to do apprenticeships or work placements with established manufacturers in the US. Participants may need to undergo some kind of intensive pre-placement training and education to make sure they are ready to adapt to the challenges of foreign workplaces, but that is very doable. After a year or two they can return to Malawi and drive the domestic sector forward.

There are challenges. Firms may be reluctant to give potential future foreign competitors an insider’s view of their business practises. What’s more, apprentices usually don’t start to earn their keep until a few years down the line. Firms take them on in the hope they will stay on and pay back that investment in the future. Clearly this won’t happen if they leave after a year. And there is the risk that participants would disappear into the ranks of the informal economy when their placement ends, and their visa expires. But even if this happens, the domestic country will benefit from their remittances. The $800bn in remittances sent in 2022 were a key source of growth in low-income countries.

Big questions remain – like who should run this and who should pay for it? There are options. It could be a programme funded by aid budgets and run by donors. The FCDO, for example, could select promising workers from countries in which they have a strong presence and fund placements for them in UK companies, working closely with the UK’s Institute for Apprenticeships and Technical Education. It is done for university scholarships so why not professional placements? Donors and governments could also incentivise private companies in any number of ways to do it themselves. Another option could put domestic governments in the driving seat by introducing requirements for multinational companies wanting to operate in their country to send local staff abroad for extensive training.

No doubt some firms in high-income countries would need some convincing to take part. But these are not unsurmountable barriers. Arms can be twisted; incentives offered. The scheme could even be sold to these firms as the beginning of a strategic partnership with high growth foreign firms, a first step towards expansion into new markets. Or, more cynically, content for the CSR section of their website. But you never know, it’s also possible that host firms could learn something from the new perspective and experience these employees would bring.

Overall, this really isn’t such a radical idea. Citizens of low-income countries have been coming to high-income countries to work for centuries – it’s called immigration. And we know this delivers significant economic development benefits when these immigrants return to their home country (see here for example). There is a strong case then for a more deliberate and targeted scheme, where relevant skill development is the priority and economic development the end goal.

The details can be worked out, tailored to the needs of the sending and receiving countries. And it’s just one idea among a range of possible interventions to raise labour productivity. But every little helps, and when the stakes are this high, we should be ready to try a range of interventions and see what sticks. A new group of workers fresh from the world’s most productive workplaces might just be able play an important part in the industrial development story of sub-Saharan Africa.