Productivity and Exports: Engines of Economic Growth

Understanding the Synergy of Productivity and Exports for Economic Prosperity

Being able to competitively export (export readiness) is a key factor in the growth of Low-income countries to Middle-income and beyond. Increasing labour productivity is crucial in the early stages of growth towards this goal. And this relationship between labour productivity and export growth is something we will be unpacking in this article.

Defining Labour Productivity: The Cornerstone of Economic Development

Mama Rehema works making aggregate, manually. She sits on the side of the road in Kigoma with a bunch of her friends and breaks stones into smaller and smaller pebbles until they are the right size for use in concrete. This labour probably nets her around 1 USD per day or 0.1 USD/hr, and in any high-income country this is done by mechanical crushing machines. However, due to poor overall labour productivity within Tanzania, and the lack of industries that can increase the productivity of her work, this is her best labour use for her time.

Labour productivity is defined as “total output” divided by the “total hours worked”, and this is usually measured in USD/hr. Manufacturing that is very reliant on labour is obviously particularly impacted by labour productivity. Let’s use the example of a textiles factory that produces shirts (we’ve previously talked about as a gateway to growth). If an average worker here makes 10 shirts in an hour, the labour cost per shirt is the worker's hourly wage divided by 10. Increase productivity so that a worker produces 15 shirts per hour, and the labour cost per shirt decreases. Driving down labour costs is crucial in an industry where price often dictates the winner. The more shirts a factory’s workforce can make in an hour, the more competitive it is not just domestically, but internationally too. And so, as labour productivity rises, so too do exports.

The benefits of boosting labour productivity should also sooner or later show up in workers’ pay packets. Bangladesh, which is the current world powerhouse for low level garment manufacturing, is now beginning to see labour productivity feeding into higher wages. Since 2005 productivity countrywide has more than doubled from 3.15 USD/hr to 6.38 USD/hr in 2019. The unions there are currently requesting a raise in the minimum wage for entry level workers to 1.14 USD/hr up from 0.4 USD/hr. As Bangladesh increases its labour productivity it begins to move up the value chain and pay its workers more. This presents an opportunity for countries with lower wages to fill the gap it leaves behind.

Labour Productivity in Low-Income Countries: A Comparative Analysis

Labour productivity in Low-income countries, unsurprisingly, lags behind global standards. Data from the International Labour Organisation shows the wide disparities between Low-income Countries and High-income Countries. In Tanzania, the average worker creates 2.77 USD of value an hour. The average worker in Italy creates 56.49 USD an hour, more than 20 times more.

Low-income Countries also lag a long way behind Middle and High-income countries; and unfortunately, this productivity gap is widening. This can be seen in the chart below, which shows percentage increases in hourly wages by country income level. Of course, there is a fair bit of selection bias here. The list of Low-income countries has dwindled since 2005, and those who have reached Middle-income status are likely those who have enjoyed strong labour productivity growth. So, to a certain extent we would expect those who remain Low-income to have had poor growth in labour productivity. All the same, it demonstrates that there remains a group of countries at the bottom of the pile that are becoming increasingly left behind.

Unpacking the Impact of Exports on Labour Productivity

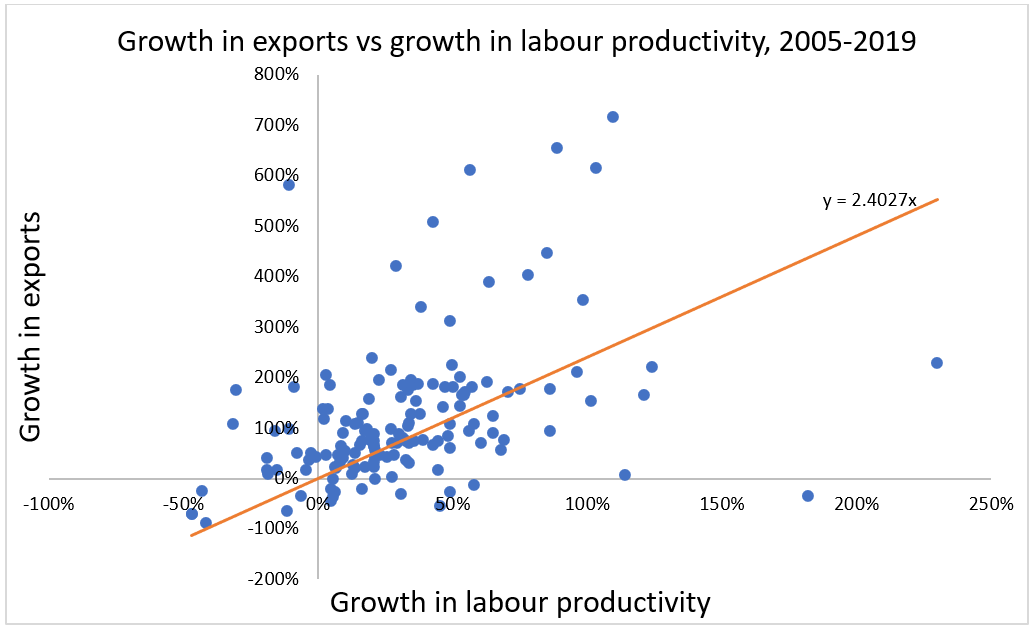

The low labour productivity of Low-income countries is holding back their ability to export and without exporting their labour productivity is not increasing. This link between increased exports and labour productivity/wages can be seen in a rough and ready analysis of labour productivity and export data. Below, 151 countries are plotted by their growth in exports vs their growth in labour productivity between 2005 and 2019. As expected, this suggests there is indeed a positive relationship between export growth and labour productivity increases; roughly speaking, a doubling of productivity correlates to a 5x increase in exports.

The relationship shown above certainly isn’t uni-directional from productivity to exports. Causation of course runs both ways but it’s a virtuous cycle. Increased labour productivity leads to increased exports and then in turn that boosts productivity through multiple channels including:

Increased efficiency through export market exposure.

Increased specialisation and economies of scale.

Overall increased labour capacity and skills in the economy which translates across different industries.

Increased investment and capital intensity of industry.

Strategies for Improving Productivity and Kickstarting Export Growth

So how does a country improve its labour productivity and get this virtuous cycle rolling? This is a very hard question, if it were easy there would be no poor countries. Bar massive infrastructure investment (which is often beyond the budgets of most low-income countries), countries must work to create a policy and regulatory environment that fosters growth in labour productivity through low-level manufacturing and exporting. Using our textiles example again, this would mean:

Incentivising companies to export through tax breaks which are linked to export incomes, and scaling these back if exports aren’t achieved.

Focusing financial institutions on cheap debt to companies engaged in export activities.

Simplifying and reducing administrative burden and overhead for export based industries.

Setting up free trade zones and industrial areas that are genuinely amenable to export industries.

Forcing parastatals (ports, utilities, etc.) to focus on the infrastructure that does exist to prioritise exporting industries.

Once these are in place and working properly (which isn’t always a given, and there are myriad instances where the regulations and policies exist, but aren’t properly implemented), then manufacturers will come, and in turn give Mama Rehema the option for higher wages than making aggregate. Focusing on building up exports with an eye on increasing labour productivity should be the primary focus of any low-income country’s industrial policy. The potential gains are on different scales to anything else that can be done.