A Dispatch from Burundi

A little country you’ve probably not really thought too much about before.

Your correspondent recently found himself in the small central African republic of Burundi. Burundi is stunningly beautifully. Situated on the eastern shore of Lake Tanganyika the landscape rises into lush hills and mountains. But being bordered by Tanzania, DRC, and Rwanda, Burundi is both in a “bad neighbourhood” and landlocked; two of Paul Collier’s four traps that inhibit economic growth (the other two are the conflict trap and the natural resource trap). With these geographical constraints, transformative economic growth was always going to be hard to achieve in Burundi.

A brief (and incomplete) history of Burundi

After gaining independence from Belgium in 1962, Burundi did not have an easy first few decades. A coup in 1966 ushered in an era of one-party rule. As in its more well-known neighbour Rwanda, bouts of ethnic violence, civil war, and two episodes of attempted genocide wracked the country through the 1970s until the mid 1990s. Hundreds of thousands of people died, more fled, and the violence left Burundi one of the poorest countries in the world. With this protracted conflict, Burundi fell into a third of Collier’s traps.

A period of stability followed the Arusha Accords which lasted until 2015 when the then President Pierre Nkurunziza announced he would run for a constitutionally questionable third term. A favourable ruling from the constitutional court (for Nkurunziza), a failed coup, over 100,000 refugees into neighbouring countries, and a boycotted election later, Nkurunziza was re-elected. In 2020 a more contested, although still contestable, election was held with Nkurunziza surprising many and choosing not to run again. His hand-picked successor Évariste Ndayishimiye won handily with 71% of the vote. In a macabre coda, Nkurunziza died one day after Ndayishimiye was announced as the winner. Aged only 55, the cause of death was announced as cardiac arrest.

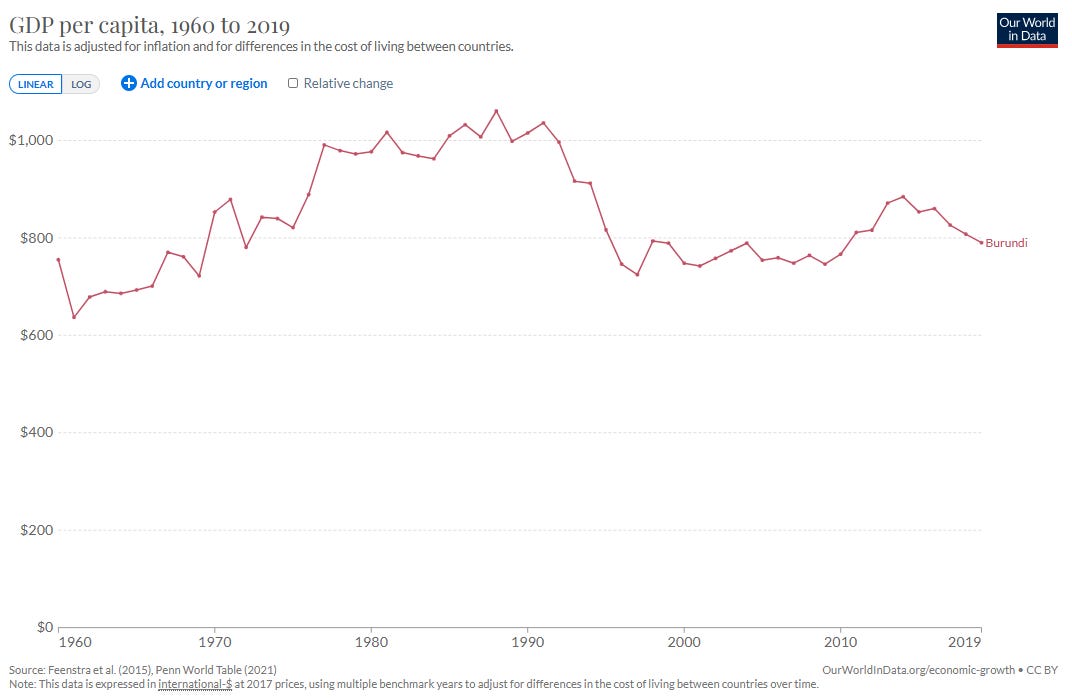

This torrid political history has not been conducive to economic growth. The 12 million Burundians remain as poor as they were at independence, with a GDP of ~$800 per capita (PPP). While currently very peaceful and a wonderful place to visit, Burundi is yet to implement the required policies or achieve the extended political stability to allow economic growth to take root.

It's All About Those Benjamins…

What follows are some anecdotes and observations from time in Burundi and from conversations with various businessowners.

Burundi is a not a large exporter. According to the UN’s Trade Map, Burundi exported just $75M worth of goods in 2021; that’s $27M less than the rocky outcrop of Gibraltar. Only nine countries exported less goods; they are all tiny island states in the Pacific or Caribbean such as Palau or Grenada. With an export sector this small, Burundi would always struggle to build a large reserve of foreign currency. Unfortunately, government policy is making this harder still. The government holds the exchange rate artificially low at around 2,500 Burundian Francs to the US Dollar. This is sometimes done by governments to try and dampen inflation but it’s a policy that can only really work in the short term. Dual exchange rates cause market distortions which become entrenched and then the pain to correct course grows by the day.

On the streets of Bujumbura a dual currency exchange system has emerged with dollars being sold for 3,500 Francs and above. This enforced scarcity of dollars means that importers’ bills are more costly. Eventually they run too high and companies just stop importing. Such is the case with petrol.

No Cars Go…

Since February there has been a shortage of fuel as the importers can’t get dollars to pay their suppliers. Obviously ruinous for the functioning of the country, this petrol shortage has basically forced activity outside Bujumbura to grind to a halt. Buses and shared taxis don’t leave until the afternoons only once they are absolutely (over)full with people. Black market petrol can sometimes be found in Bujumbura after several hours of searching but for at least triple the official price. If a petrol station does have petrol, vehicles queue for hours and cars are let in one by one by police who control the flow with barbed wire barricades.

Take the Money and Run…

The dollar shortage has many other perverse consequences. To try and increase dollar deposits at the central bank (but obviously stopping short of letting the Franc float freely), the government forces exporters to deposit the full dollar value of each consignment exported with the central bank within a week of export. The exporter can then withdraw this money as Francs at the official (low) rate. In theory these dollars should come from the exporters’ customer but of course in practice it usually just comes from the exporter themselves; not all export contracts are paid within a week. If you don’t deposit your dollars, you will not be granted an export permit for your next shipment. This policy functions as a large tax on all exports. Countries who seek to grow their economies should incentivize exports, not hamstring them with taxes. As a general rule, people don’t love paying taxes so the policy also encourages smuggling to avoid the official process.

Pour Some Sugar on Me…

Burundi grows sugar cane in relative abundance. Much of this sugar used to end up with domestic consumers and industry. However, producers can smuggle this sugar across the porous land and lake borders with DRC and get paid in dollars. This money is repatriated as cash, sold at the black market rate, and the sugar producer is far ahead of where there would be if they sold in country in Francs or exported officially. This happens so much that there is a shortage of sugar for sale in Burundi. Sugar was even rationed by the government so that shops could only sell 1kg per person at a time. Due to shortages the local bottler of Coca-Cola switched to producing only Coke Zero and Fanta Citron; regular Coke and Fanta Orange just use too much sugar.

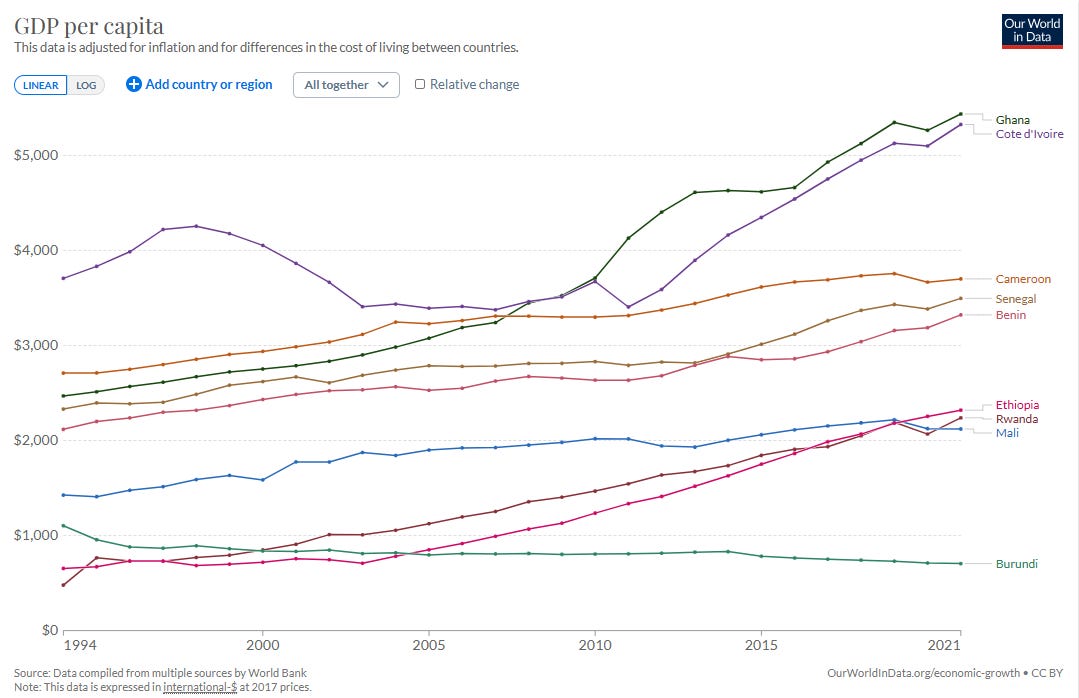

The Only Way is Up…

Given its history of unrest and its challenging geography, the odds are stacked against Burundi. But though it’s tempting to be fatalistic, there is nothing inevitable about Burundi’s plight. Over the last couple of decades, countries across the African continent with histories of violence and mismanagement have achieved solid economic growth. Progress is possible then. But it requires sound, forward-thinking, and sometimes brave, policymaking. Abolishing the dual exchange rate and promoting rather than punishing exports would be good places to start. Burundi’s leaders should focus on removing harmful distortions and implementing reforms designed to get the country moving. That way they can deliver not only Fanta Orange for Burundians, but perhaps some economic prosperity as well.